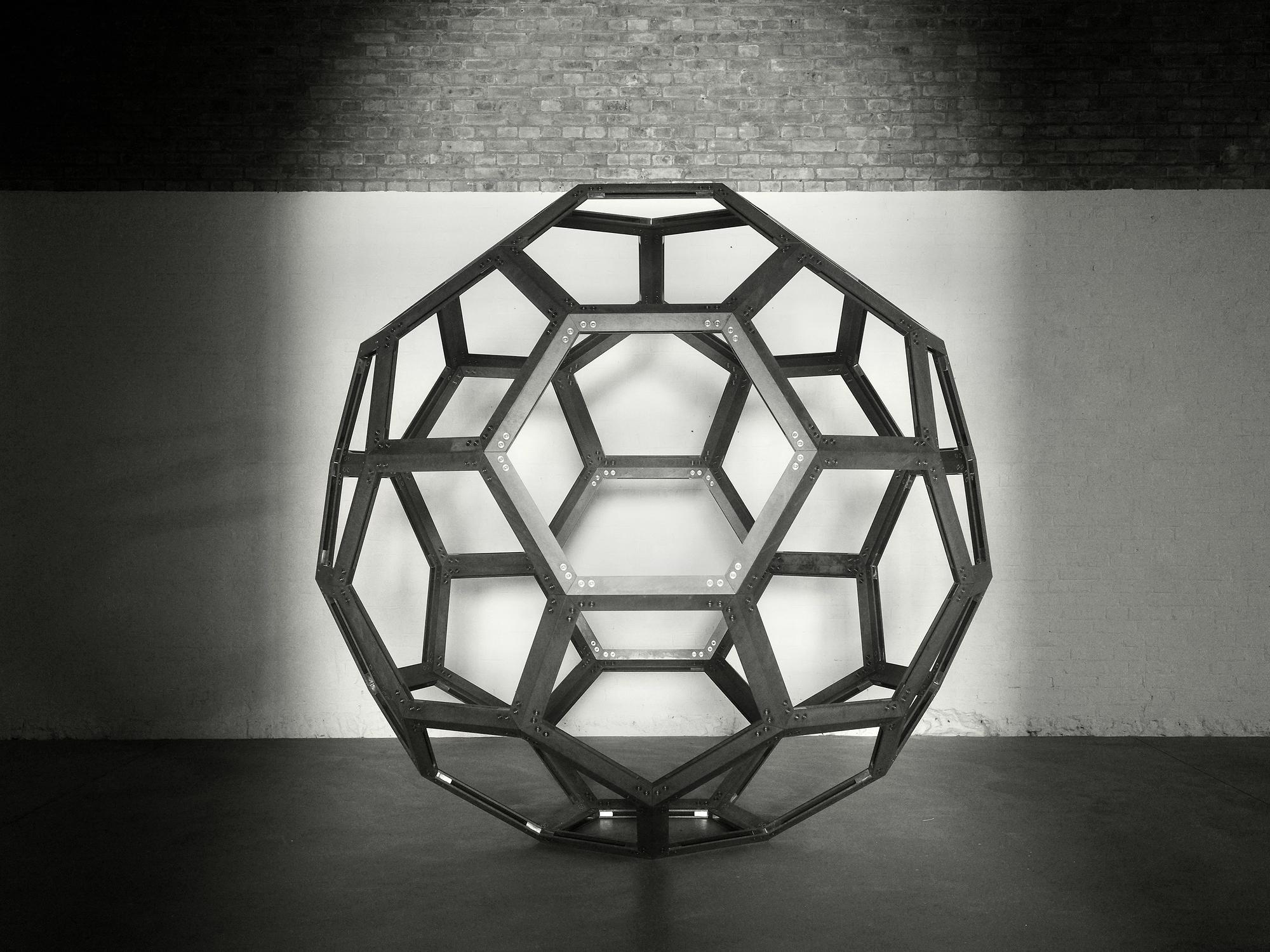

Faktura 10—Jannis Kounellis, Untitled, 1997/2025

Faktura 10, a core initiative of RIBBON International, presents “Jannis Kounellis: Untitled (1997/2025).”

In 1997, a rare opportunity arose to work with the artist Jannis Kounellis in Kyiv within the apse of what was, at that time, the Soros Center for Contemporary Art, housed in a renovated baroque-era building that had served as the original location of Kyiv-Mohyla Academy. Kounellis’s proposal was simple yet expansive—an intervention comprising steel I-beams mounted along the length of the nave from which would hang a series of church bells. Kounellis’s only conditions for the bells were that they be historic in origin and made in Ukraine. The artist’s plan corresponded with his role as a central figure of the Arte Povera movement, which possessed, according to Germano Celant, “a new attitude for taking repossession of a ‘real’ dominion over our existence [leading] the artist towards continual forays outside of the places assigned to him.”

Throughout the project, Kounellis often spoke about Ukraine’s avant-garde prior to and after 1917. Discussions ventured into the writings of Ukrainian painter David Burliuk, who characterized “deconstruction as the opposite of construction” and believed in the ability of construction to be “shifted or displaced.” Burliuk revived the term facture (a reference to the texture of a painting’s surface) to infer a process of investigation of materiality. While it was perhaps not recognized by Kounellis as such, his observations and perspectives recalled these historical inquiries—particularly in his professing that “painting has a capacity for synthesis, so an idea of composing in space, all paintings have an order of composition that is always more ancient than they are.”2

Reconstructing Kounellis’s work from 1997 in Ukraine today is to recognize that Kounellis was an artist informed by war, having lived through World War II and the Greek Civil War. His integration of industrialized materials common to wartime production as remnants of destruction, spoke as much to the postwar human condition as it did to fracture and disruption. As the artist noted, “since the war, we have only contradictions.”3

Amid a continuing war waged by Russia, the resurrection and reconstitution of this project in June 2025 stands as a gesture toward the autonomy of art and life. The original project was one of contradictions, and the procurement of the bells remains enigmatic (and was made possible only through some sleuthing by an architectural historian from the western region of Ukraine). Nevertheless, Kounellis’s work made evident that the church bell represented a dialectical object. For this iteration, the origin of the bells is transparent and cooperative—the Museum of the Bells, within Lubart’s Castle in Lutsk, has loaned fourteen examples, dating from 1688 to 1925, from both Orthodox and Catholic origins, and from various regions of Ukraine. In addition, bells have been generously loaned by Kyiv’s St. Sophia Cathedral. And—as was requested by the artist in 1997—clappers have been cast for those bells for which none exist, not for the purpose of being rung, but to reestablish the potential of their resonance.

Jannis Kounellis Untitled, 1997/2025 is curated by Marta Kuzma, Artistic Director and Chief Curator, Faktura 10, and Professor of Art at the Yale School of Art. The project has been made possible through the cooperation of the Archivio Kounellis in Rome and the National University of the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy in Kyiv, Ukraine. The original project was also curated by Marta Kuzma, then the Founding Director of the Soros Center for Contemporary Art in Kyiv (1990–2000) in cooperation with Nicolo Asta and Giulio Alessandri.

Jannis Kounellis, Untitled, 1997/2025 is part of Faktura 10, a core initiative of Ribbon International. It is made possible with the cooperation of FORMA in Kyiv.

- Germano Celant, “Arte Povera: Notes on a Guerilla War,” Flash Art 5 (Nov.–Dec., 1967).

- Jannis Kounellis, “The Traveler in the Labyrinth: Collected Thoughts & Writings of Jannis Kounellis,” in Jannis Kounellis in Six Acts, trans. Vincenzo de Bellis (Walker Art Center, 2022), 213.

- Kenneth Baker, “Jannis Kounellis and the Reenchantment of Contradiction: Diverting Fact to Possibility,” Artforum (February, 1987), 100.

The Opening Program on Sunday, June 15

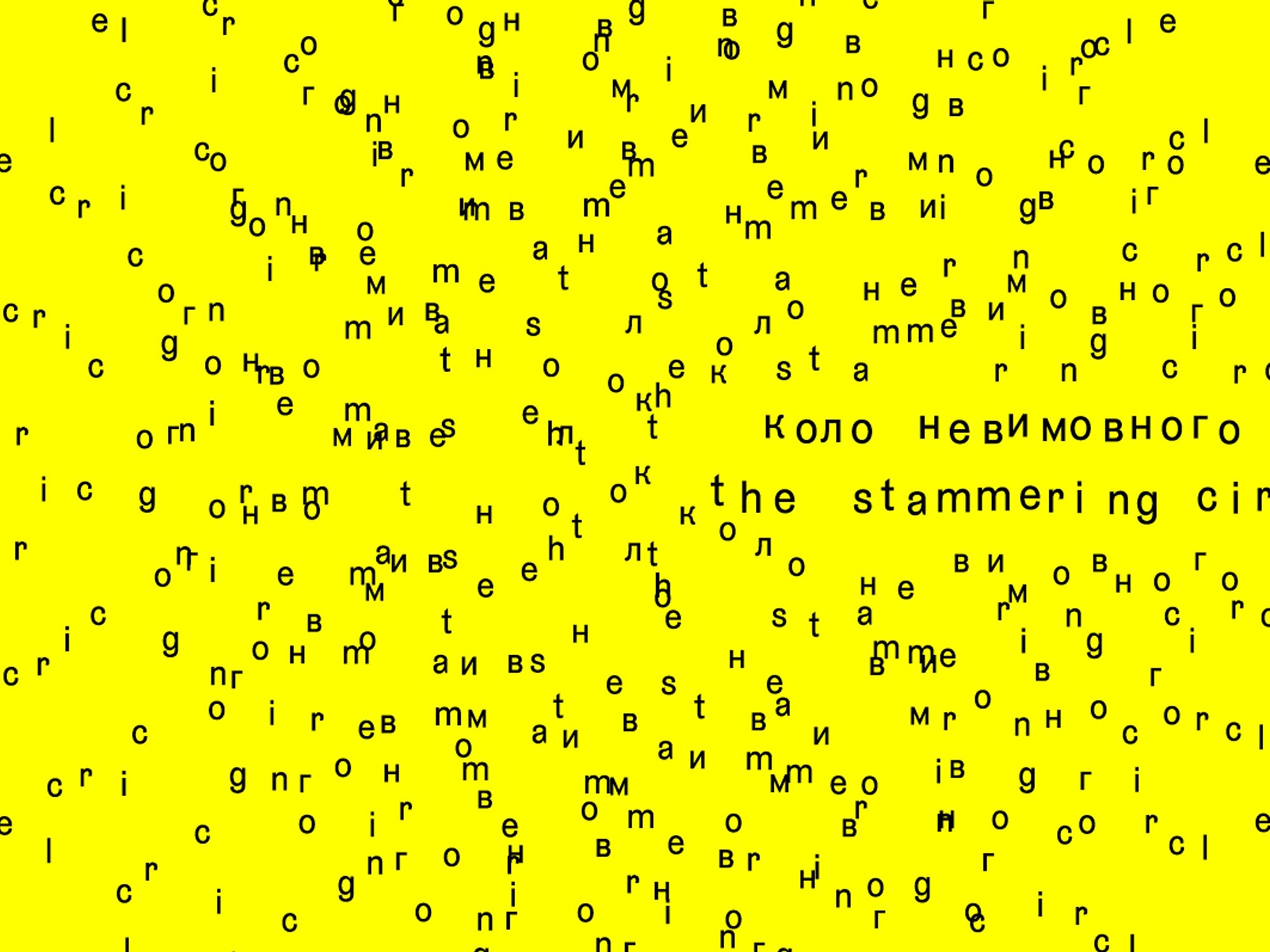

Small Song

Isaac de Judea and Olga Ostroverkh

Curated by Sasha Andrusyk

The opening performance by Isaac de Judea and Olga Ostroverkh, as accompanied by Pavlo Kosenko and Oleksiy Khokhun is a shared practice of cante de fiesta and cante chico — which, translated into light-hearted song, is the festive branch of flamenco-associated dance forms such as alegrías and tangos. The choice of dance form is not intended as aesthetic but liturgical. That is, according to the teachings of Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, founder of the Breslov Hasidic movement, the period of mid-June obliges Hasidim to cultivate and transmit joy. “It is a great mitzvah to always be happy,” Rabbi Nachman writes. In this context, mitzvah refers not simply to a good deed, but to a divine commandment: joy as a religious obligation.

Isaac de Judea, originally from Granada and now based in Uman, the site of Rabbi Nachman’s gravesite, observes Breslov teachings in both daily life and artistic practice. In this particular performance, de Judea opts for cante chico, considered less solemn than the distinctive melodic style cante jondo that refers to death, anguish, and despair. Although “chico” may literally mean small, its implementation in this respect does not imply lesser technical skill, rather, reflects a cultural framing of these songs as informal or domestic. Many of the most personal and versatile flamenco expressions take place within this register—within an intimacy this performance adheres to. Most of lyrics sung by Isaac have been authored or adapted by himself, following a longstanding tradition within flamenco where singers compose their own verses—among them tangos de Granada, tangos de Kyiv, tangos de Uman, and alegrías referencing Jewish histories in both Cádiz and Uman.

Flamenco has a complex relationship to poverty, rooted in its origins to marginalized communities. It has served as a powerful symbol of resistance. Although it is rooted in different cultural and historical contexts, flamenco shares in Arte povera a commitment to transformation through austerity. As flamenco used minimal resources to focus on the essential elements of performance, often in unconventional spaces, Arte povera rejected the superfluous in favor of artisanal materials and the processural, as expressed in teatro povero. Flamenco, particularly in its traditional settings, foregrounds voice, breath, compás, and bodily presence. While it has often engaged with spectacle, it remains structurally anchored in constraint, repetition, and transmission. This performance underscores that common ground. Here, joy is not performed for effect,but enacted as discipline. As Rabbi Nachman taught: “If you believe you can damage, then believe you can repair.”

The Garden at the Kyiv-Mohyla Academy

Ukrainian artist Nina Dyrenko and arborist Volodymyr Vitrogradsky have been invited by Faktura 10 to work in cooperation with the woody plants and herbaceous plants of the Kyiv Mohyla property adjacent to the Old Academic Building of the Kyiv Mohyla Academy. Inhabited by overgrown trees and shrubs that include mulberries, maples, lindens, spruces, elderberries, viburnums, dogrose, birches, cherries, chestnuts, apricots, plums, peaches, lilacs, and oaks, that plant life was in dire need of care and cultivation.